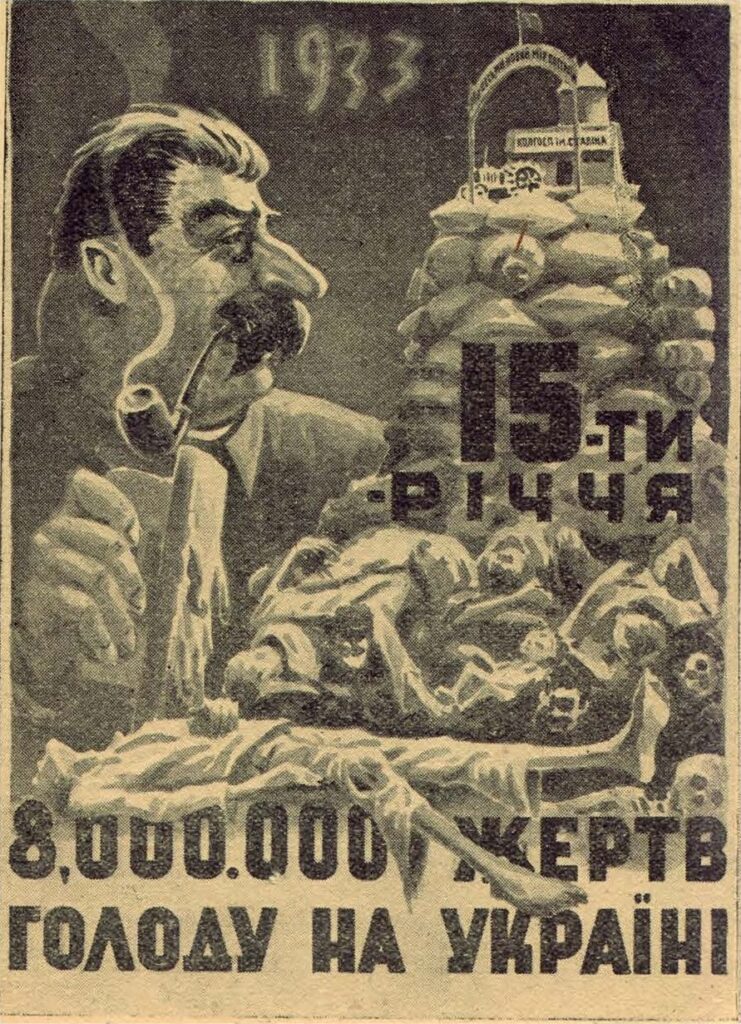

Red Famine: Stalin’s War On Ukraine, by Anne Applebaum, details the Holodomor, a famine imposed by USSR/Stalin on Ukraine that killed millions of people in the early 1930s. Applebaum explains that the

“term [is] derived from the Ukrainian words for hunger – holod – and extermination – mor.”

Citing experts, Applebaum places the “number of missing Ukrainians” at 4.5 million:

“These figures include all victims, wherever they died – by the roadside, in prison, in orphanages.”

Applebaum’s book cites new scholarship and primary documents to tell the story of the imposed famine:

“Several sets of directives that autumn [of 1932], on requisitions, blacklisted farms and villages, border controls and the end of Ukrainization – along with an information blockade and extraordinary searches, designed to remove everything edible from the homes of millions of peasants – created the famine now remembered as the Holodomor. The Holodomor, in turn, delivered the predictable result: the Ukrainian national movement disappeared completely from Soviet politics and public life.”

Applebaum explains that the term “genocide” is not used for the Holodomor:

“…it is now difficult to classify the Ukrainian famine, or any other Soviet crime, as genocide in international law. This is hardly surprising, given that the Soviet Union itself helped shape the language precisely in order to prevent Soviet crimes, including the Holodomor, from being classified as ‘genocide.'”

The USSR added a cultural famine, as well:

“The extermination of the intellectual class was accomplished by the extermination of their words and ideas.”

Among many cultural losses, a passage about the loss of music reveals how powerful social influences can suddenly be hidden and forgotten:

“Within a decade musical traditions were lost too. Traditionally, young people had gathered together at somebody’s house, unmarried girls helping out with weaving or embroidering while boys sang and played music. This custom of dosvitky – ’till dawn’ – celebrations gradually ceased, as did Sunday dances and other informal musical gatherings. Young people were told instead to meet in the Komsomol, and formal concerts replaced the spontaneous village music-making.”

The famine and mass-deaths of the Holodomor were not a secret in Russia, and Applebaum quotes a student from the time period, whose reflections on “verbal camouflage” to tolerate such terror and mass-murder is sobering in our dark time:

“As he [student Viktor Kravchenko] explained years later, he had … deliberately allowed himself to succumb to a form of intellectual blindness. Kravchenko spoke for many when he described it:

‘To spare yourself mental agony you veil unpleasant truths from view by half-closing your eyes – and your mind. You make panicky excuses and shrug off knowledge with words like exaggeration and hysteria.’

“The language of the propaganda also helped mask reality:

‘We communists, among ourselves, steered around the subject; or we dealt with it in the high-flown euphemisms of party lingo. We spoke of the “peasant front” and “kulak menace,” “village socialism” and “class resistance.” In order to live with ourselves we had to smear the reality out of recognition with verbal camouflage.'”

Applebaum quotes another journalist to make the point: Eugene Lyons, Moscow correspondent for United Press:

“There was no more need for investigation to establish the mere existence of the Russian famine than investigation to establish the existence of the American depression. Inside Russia the matter was not disputed.”

(We should note that Lyons was not a person of the people. Scholar S. J. Taylor writes that,

“In Lyon’s estimate, the Red Decade of the 1930s would result eventually in the infiltration of ‘youth, Negro, consumer, women’s liberation, anti-pollution and other current movements.’ It was the kind of thinking that would usher in the McCarthy era and its peculiarly American version of purgation and self-mutilation.”)

While Ukrainian people’s oral histories have kept the fact of the Holodomor alive, it was deeply hidden by the USSR and others for many decades, only coming to public light in the 1980s and 90s. Along the way, Applebaum explains why; while also explaining the 2022 Russian invasion and occupation of Ukraine in a way that many USAers might not have appreciated:

“…disdain for the very idea of a Ukrainian state had been an integral part of Bolshevik thinking even before the revolution. In large part this was simply because all of the leading Bolsehviks, among them Lenin, Stalin, Trotsky, Piatakov, Zinoviev, Kamenev and Bukharin, were men raised and educated in the Russian empire, and the Russian empire did not recognize such a thing as ‘Ukraine’ in the province that they knew as ‘Southwest Russia.’ The city of Kyiv was, to them, the ancient capital of Kyivan Rus’, the kingdom that they remembered as the ancestor of Russia. In school, in the press and in daily life they would have absorbed Russia’s prejudices against a language that was widely described as a dialect of Russian, and a people widely perceived as primitive former serfs.”

To further bring the point home, she quotes Ukrainian poet/writer Ivan Drach:

“The first lesson which is becoming an integral part of Ukrainian consciousness is that Russia has never had and never will have any other interest in Ukraine beyond the total destruction of the Ukrainian nation.”

And why not?

“As in 1932, when Stalin told Kaganovich that ‘losing’ Ukraine was his greatest worry, the current Russian government also believes that a sovereign, democratic, stable Ukraine, tied to the rest of Europe by links of culture and trade, is a threat to the interests of Russia’s leaders. After all, if Ukraine becomes too European – if it achieves anything resembling successful integration into the West – then Russians might ask, why not us?”

After the invasion and occupation, Applebaum presents an example of a Twilight Zone-esque animosity between formerly friendly neighbors, that always happens when bullies take over – what The Hague called “the accumulated evil of the whole”:

“One testimony, written by a Jewish trader, Symon Leib-Rabynovych, when twenty members of ‘Struk’s gang’ took over in 1919. On the first evening the Jews of the village were taken hostage until they agreed to pay 1,800 rubles. A few days later most of them fled temporarily, following a Bolshevik attack on the village. When they returned, they discovered that their homes had been plundered and their possessions distributed among their neighbours. Leib-Rabynovych went to one of them and asked for his feather bed back:

‘He fell on me like a wild beast; how did I dare to demand of him, the head man of the village? He would arrest me and hand me over to the Strukists as a communist. I saw that some change had taken place in my neighbour. He had previously been peaceable, and extraordinarily conscientious, and had always been kind to me. I understood that I could not stay any longer in the village. I had to get away to save my life.'”

In the abyss of darkness, rays of light do shine through Applebaum’s book, like the enemy-admitted fact that the Ukrainian resistance was led by women:

“By the end of March 1930 the OGPU [KGB] had recorded 2,000 ‘mass’ protests, the majority of which were exclusively female, in Ukraine alone. At the Ukrainian Party Congress in the summer of 1930 several speakers referred to the problem. Kaganovich, no longer head of the Ukrainian Communist Party but still keenly interested in Ukrainian affairs, declared that women had played the ‘most “advanced” role in the reaction against the collective farm.’ The OGPU explained this phenomenon, naturally, as evidence of the influence of the ‘kulak-anti-Soviet-element’ on their ignorant wives and daughters. More propaganda work and agitation among women would surely solve the problem.”

The USSR maintained the same tunnel vision when it came to the refugees they created as they continued to smash Ukraine:

“What really concerned the Soviet authorities was the political significance of this mass movement of [starving] people. All across the Soviet Union, in the far north and far east, in the Ukrainian-speaking territories of Poland and in Ukraine itself, itinerant Ukrainians were not only spreading news of the famine, they were bringing their allegedly counter-revolutionary attitudes along with them. As their numbers increased dramatically, the Soviet government finally declared there could no longer be any doubt: ‘the flight of villagers and the exodus of the Soviet government . . . and agents of Poland with the goal of spreading propaganda among the peasants.'”

In fact, there does not seem a single thing a Ukrainian person could do, even staying alive, that the USSR wouldn’t consider “spreading propaganda.”

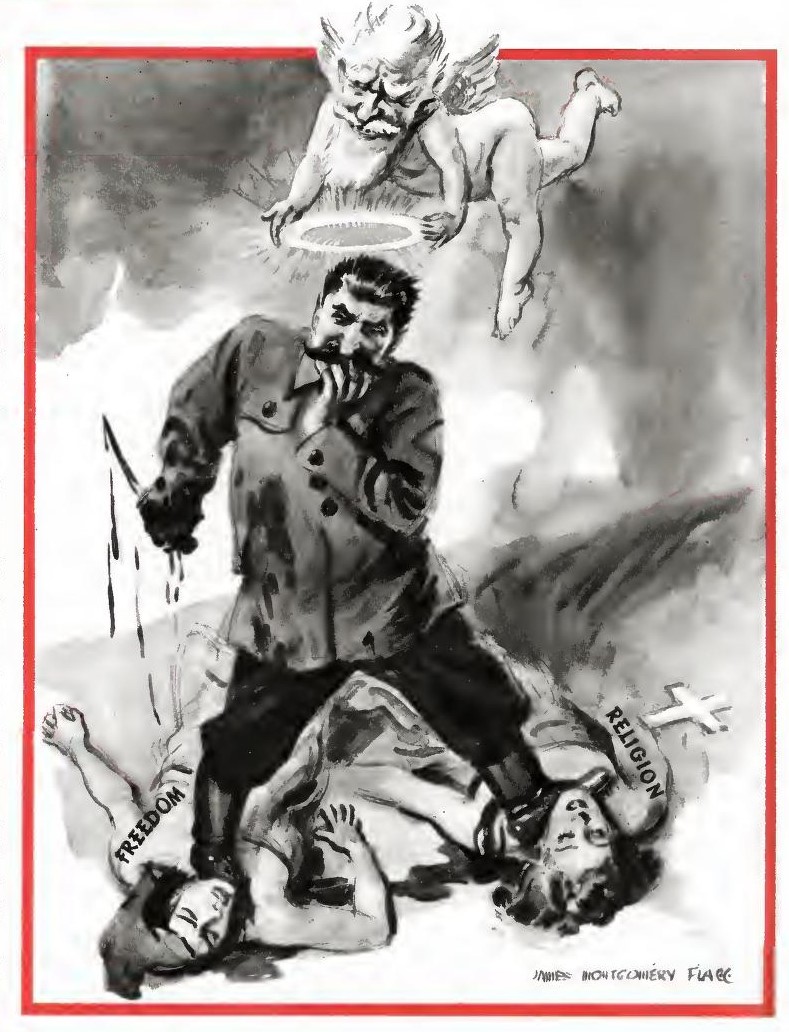

The New York Times and the Holodomor: Is Journalism Worth Lying For?

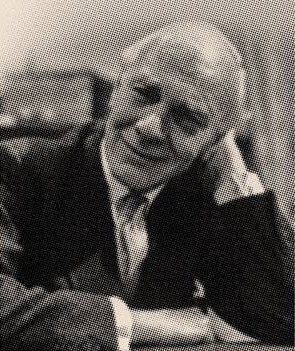

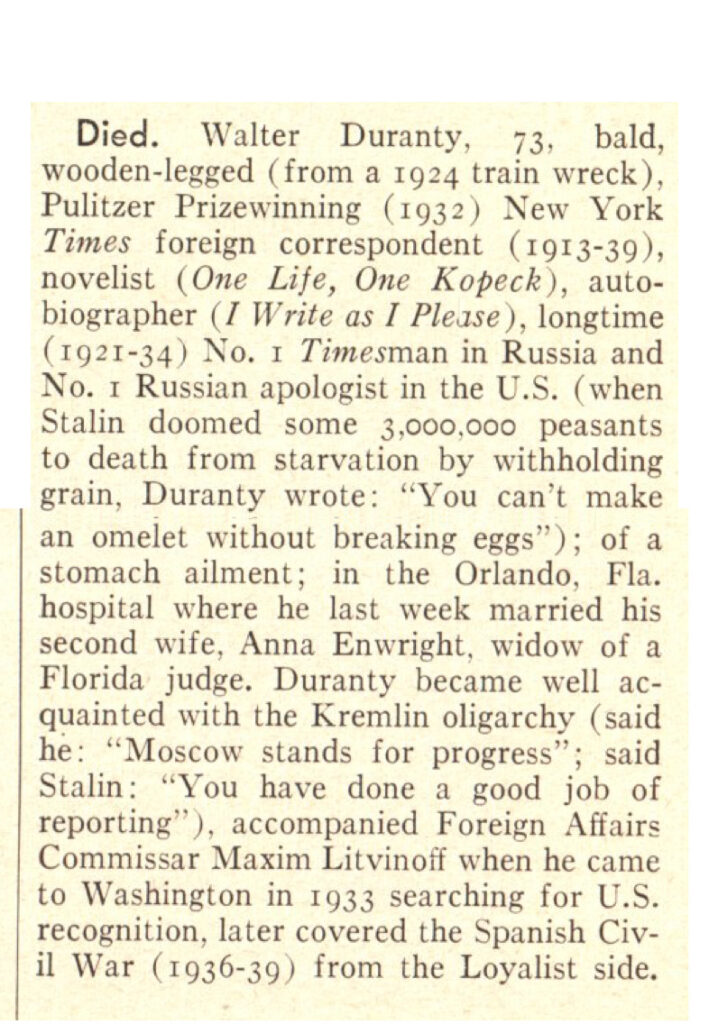

Deep into the book, Applebaum devotes Chapter 14 to “The Cover-Up” – and everyone’s favorite fit-to-print publisher takes the lead: The New York Times, and a now-forgotten (or disowned) Pulitzer-winning reporter, Walter Duranty, who received his reward in full.

“The Cover-Up” is not just deeply shaming to The Times, but illustrates how essential, and tightly controlled Point Of View is by our media, and that even intrepid journalists willing to sacrifice themselves to get at the truth, and tell it, cannot necessarily overcome the lies and obfuscations with truths. GWBush invaded Iraq, with great assistance from The Times, which continues the fascist coup to this day by “sanewashing” Trump and the entire fascist Republican party. Consistency is no mistake or accident. As Applebaum explains, then as it is today:

“Extra rewards were available to those who played the game particularly well, as the case of Walter Duranty famously illustrates. Duranty was the correspondent for The New York Times in Moscow between 1922 and 1936, a role that, for a time, made him relatively rich and famous. Duranty, British by birth, had no ties to the ideological left, adopting rather the position of a hard-headed and skeptical ‘realist’ trying to listen to both sides of a story. ‘It may be objected that the vivisection of living animals is a sad and dreadful thing, and it is true that the lot of kulaks and others who have opposed the Soviet experiment is not a happy one,’ he wrote in 1935. But ‘in both cases, the suffering inflicted is done with a noble

purpose.’

[One can almost hear Madeline Albright declaring that a half-a-million dead Iraqi children were “worth it.”]

“This position made Duranty enormously useful to the regime, which went out of its way to ensure that he lived well in Moscow. He had a large flat, kept a car and a mistress, had the best access of any correspondent, and twice received coveted interviews with Stalin. But the attention he won from his reporting seems to have been the primary motivation for Duranty’s flattering coverage of the USSR. …Duranty’s missives from Moscow made him one of the most influential journalists of his time.”

Playing the game meant and means conforming one’s language to conceal meaning:

“The [Soviet] censors also began to watch dispatches for covert reporting on the famine. Some phrases were allowed: ‘acute food shortage,’ ‘food stringency,’ ‘food deficit,’ ‘diseases due to malnutrition,’ but nothing else.”

Much like when Ronald Reagan reclassified “ketchup” as a vegetable, and changed “hunger” to “food insecure.”

S. J. Taylor’s biography of Duranty, Stalin’s Apologist, addresses these “extra rewards” journalists received. While some

“newsmen who knew Duranty personally found it a laughable proposition that he would sell out to the KGB”

it entirely – purposefully? – misses the point. Duranty didn’t need to officially, with notarized documents, become a Communist Party member and swear fealty to the KGB and Stalin. His actions and writing already showed that he was on their side. Trump doesn’t need to get Fox news to “sell out” to him – they were sold out to his point of view long before 2016.

It’s like saying that Rupert Murdoch slips envelopes of cash underneath tables to journalists who then agree to present a story in a particular way. But they wouldn’t work for Murdoch, or NYTimes or Fox or Pravda, unless they’d already accepted that media’s point of view as their own (or pretended to, the same thing in this case). Pretending that secret-back-room-cash-stuff-envelopes is how journalists/artists/professors/scientists/ect. are “bribed” to uphold abusive regimes is part of how people allow such truthful considerations to be dismissed as absurd.

Edward Herman’s and Noam Chomsky’s famous Manufacturing Consent explains

“Given the imperatives of corporate organization and the workings of the various filters, conformity to the needs and interests of privileged sectors is essential to success. In the media, as in other major institutions, those who do not display the requisite values and perspectives will be regarded as ‘irresponsible,’ ‘idealogical,’ or otherwise aberrant, and will tend to fall by the wayside. While there may be a small number of exceptions, the pattern is pervasive, and expected. Those who adopt, perhaps quite honestly, will then be free to express themselves with little managerial control, and they will be able to assert, accurately, that they perceive no pressures to conform. The media are indeed free – for those who adopt the principles required for their ‘societal purposes.’ There may be some who are simply corrupt, and who serve as ‘errand boys’ for state and other authority, but this is not the norm.”

Of those correspondents who didn’t think it was laughable, Malcolm Muggeridge was eloquent in describing Duranty’s skill, (what Belle would tell Scrooge was a “safe and terrible answer”):

“He’d [Duranty] been asked to write something about the food shortage, and was trying to put together a thousand words which, if the famine got worse and known outside Russia, would suggest that he’d foreseen and foretold it, but which, if it got better and wasn’t known outside Russia, would suggest that all along he’d pooh-poohed the possibility of there being a famine.”

Another journalist, Harrison Salisbury, described a typical inability to be humble:

“Duranty was simply incapable of reporting something that broke the pattern he had established.”

Taylor describes Duranty as “without moral commitment to his fellow beings” (something Duranty was proud of) and sums up devastatingly:

“Had Duranty, a Pulitzer Prize-winner at the peak of his celebrity, spoken out loud and clear in the pages of the New York Times, the world could not have ignored him, as it did Muggeridge and [Gareth] Jones, and events might, just conceivably, have taken a different turn. If Duranty had taken a stand, he might now be accounted one of the century’s great, uncompromising reporters. But he did not.”

It is not speculation to say that Duranty and The Times knew about the purposeful-famine, and purposefully covered it up:

“Duranty himself discussed the famine with William Strang, a diplomat at the British Embassy, in late 1932. Strang reported back drily that the correspondent for The New York Times had been ‘waking to the truth for some time,’ although he had not ‘let the great American public into the secret.’ Duranty also told Strang that he reckoned ‘it quite possible that as many as 10 million people may have died directly or indirectly from lack of food,’ though that number never appeared in any of his reporting. Duranty’s reluctance to write about famine may have been particularly acute: the story cast doubt on his previous, positive (and prize-winning) reporting.”

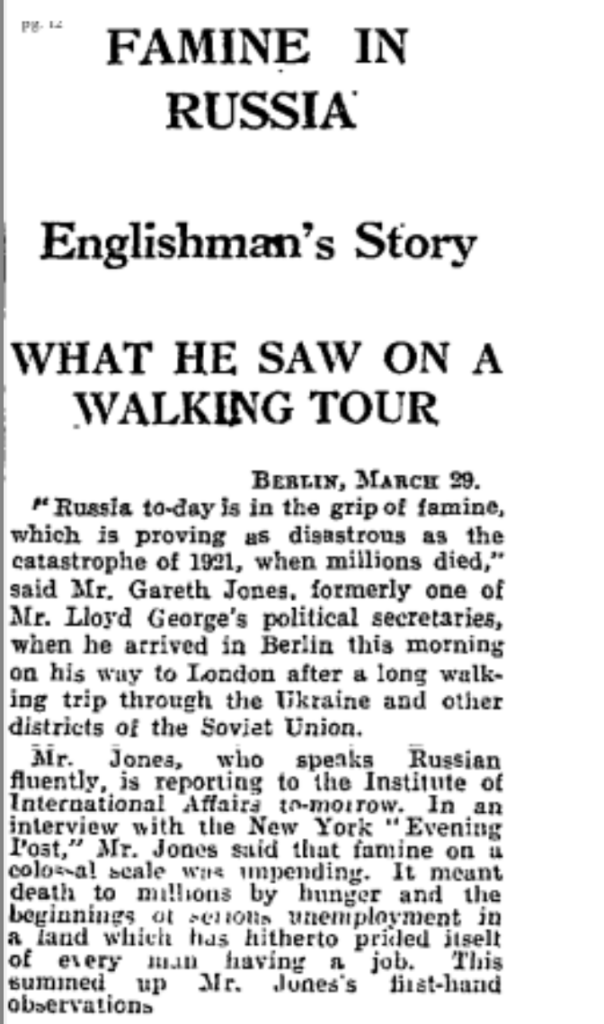

Nevertheless, journalism just keeps attracting a few people who want to learn important truthful things about the world, and tell everyone about it. In the case of the Ukrainian Holodomor, that journalist was Gareth Jones, who

“slept on the floor of peasant huts. He shared his food with people and heard their stories.”

Lyons self-consciously described Jones in a funny way, as though he knew Jones was doing journalism, but needed to undermine Jones (and journalism) to live with Lyons’ having become “a volunteer propagandist for the Soviet idea.” Lyons wrote of Jones,

“An earnest and articulate little man, Gareth Jones was the sort who carries a note-book and unashamedly records your words as you talk. Patiently he went from one correspondent to the next, asking questions and writing down the answers.”

Jones also held a press conference in Berlin, to try to get word out to the entire world, past the censors both Soviet and editorial. Applebaum tells the story through Lyons:

“Lyons meticulously described what happened:

‘Throwing down Jones was as unpleasant a chore as fell to any of us in years of juggling facts to please dictatorial regimes – but throw him down we did, unanimously and in almost identical formulations of equivocation. Poor Gareth Jones must have been the most surprised human being alive when the facts he so painstakingly garnered from our mouths were snowed under by our denials . . . There was much bargaining in a spirit of gentlemanly give-and-take, under the effulgence of [Konstantin] Umanskii’s gilded smile, before a formal denial was worked out. We admitted enough to sooth our consciences, but in roundabout phrases that damned Jones as a liar. The filthy business having been disposed of, someone ordered vodka and zakuski.’“Whether or not such a meeting actually ever took place, it does sum up, metaphorically, what happened next. On 31 March, just a day after Jones had spoken out in Berlin, Duranty himself responded. “Russians Hungry But Not Starving,” read the headline of The New York Times. Duranty’s article went out of its way to mock Jones:

‘There appears from a British source a big scare story in the American press about famine in the Soviet Union, with “thousands already dead and millions by death and starvation.” Its author is Gareth Jones, who is a former secretary to David Lloyd George and who recently spent three weeks in the Soviet Union and reached the conclusion that the country was “on the verge of a terrific smash,” as he told the writer. Mr. Jones is a man of keen and active mind, and he has taken the trouble to learn Russian, which he speaks with considerable fluency, but the writer thought Mr. Jones’s judgment was somewhat hasty…” Duranty continued, using an expression that later became notorious: “To put it brutally – you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs.”

[This is while Duranty himself was speculating privately that up to 10 million people might be killed in the famine – the broken “eggs” in the USSR-omelette.

Duranty’s prose jibes at Jones’ having “recently spent three weeks in the Soviet Union” – even though the meaning is that Jones visited places suffering from the famine, like a journalist, while Duranty did not.]

“Indignant, Jones wrote a letter to the editor of The Times, patiently listing his sources – a huge range of interviewees, including more than twenty consuls and diplomats – and attacking the Moscow press corps:

‘Censorship has turned them into masters of euphemism and understatement. Hence they give “famine” the polite name of “food shortage” and “starving to death” is softened down to read as “widespread mortality from diseases due to malnutrition.”‘

In summation, however, Applebaum writes,

“And there the matter rested. Duranty outshone Jones: he was more famous, more widely read, more credible. He was also unchallenged. Later, Lyons, Chamberlin and others expressed regret that they had not fought harder against him.”

It is a common tactic of dismissing any criticism of power, particularly powerful media, to exaggerate claims, and pretend the accusation is that “everyone’s in on it, right? The journalist, their secretary, their editor, the publisher? Sure, yeah right.”

But, unsurprisingly, this is exactly what Lyons describes:

“The need to remain on friendly terms with the censors … was for all of us a compelling professional necessity. … Forced by competitive journalism to jockey for the inside track with officials, it would have been professional suicide to make an issue of the famine at this particular time.”

[Better to lose your soul, than commit professional suicide.]

After being told they couldn’t leave Moscow “without submitting a detailed itinerary and having it officially sanctioned,” Lyons admits that,

“The same department which daily issued denials of the famine now acted to prevent us from seeing that famine with our own eyes. Our brief cables about this desperate measure of concealment were published, if at all, in some obscure corner of the paper. The world press … agreed without protest to a partnership in the macabre hoax.”

George Bernard Shaw

Applebaum also leaves room for a very instructive story about English Pygmalion writer George Bernard Shaw, in an illustrative story that explains why Shaw’s name did not appear in the Nazi’s “Black Book” list of people to arrest in England after they invaded:

“The writer George Bernard Shaw, accompanied by the MP Nancy Astor, celebrated his seventy-fifth birthday at a banquet in Moscow … in 1931. … Thanking his hosts, he declared himself the enemy of anti-Soviet rumour-mongers. When friends had heard he was going to Russia, he told the crowd, they had given him tins of food to take on the journey:

‘They thought Russia was starving. But I threw all of the food out the window in Poland before I reached the Soviet frontier.’

“His audience ‘gasped,’ recalled a journalist [Lyons] in attendance: ‘One felt the convulsive reaction in their bellies. A tin of English beef would provide a memorable holiday in the home of any of the workers and intellectuals at the gathering.'”

Lyons’ description of Shaw/Astor visiting the USSR under Stalin reads like the stories written by journalist Robert Fisk about the USA’s “green zone” in Iraq – obedient journalists (most everyone) were forbidden from going outside the “green zone” without USA escort; and obedient journalists scolded disobedient ones like Fisk because he might ruin it (having “access”) for everyone else by doing real journalism.

“From the first, the Irish bard was surrounded and cut off from contaminating contact with Russian facts by British and American yes-men for the Soviets and by Russian functionaries. They had a simple job of it. The great G. B. S. was more interested in being seen than in seeing, in being heard than in hearing. He exhibited himself at banquets, in a factory or two, on a hand-tooled collective farm, astride the Napoleon cannon in the Kremlin, wherever cameramen could get good shots of him and he could deliver better shots.

“We wondered at the time that a playwright wise in the tricks of stage effect should be taken in so completely by his hosts and guides. Then we understood that he was not taken in, but himself collaborating in the deception, with the world at large as the common dupe. The Kremlin was too good an eminence from which to thumb his nose at the conventional capitalist world, and Shaw evidently had decided not to miss the chance.

“…his main preoccupation was to make faces at the decaying bourgeois world through Soviet windows.”

Shaw, as well as being a favorite of the Nazis, was also a favorite of Italian fascists, Lyon writes in his Assignment In Utopia:

“In a book published five years later by an Italian refugee from Mussolini’s penal colony on Lipari Island (Road to Exile, by Emilio Lussu), he tells how the small library collected by the prisoners was suppressed:

‘Hundreds of volumes were confiscated as dangerous to the regime; every book on the French and Russian Revolutions, all works by Russian writers and all works by free-thinkers such as Voltaire, Mazzini, and Anatole France. Only Bernard Shaw was respected. It was a bad moment for his admirers.'”

The most instructive part of Lyons’ Shaw story is how easy it is for power-worshippers to switch teams, as though the whole thing is as meaningless as who wins or loses the football match:

“…those who take Bolshevik excesses in their stride find it equally easy to take fascist enormities in their stride. It is no accident that Shaw has praised Hitler, too.”

Lyons helps one understand why genuine and well-meaning Westerners stayed committed to USSR’s brutal totalitarianism, even as it was clear it had nothing to do with democracy or equality:

“[Western] Professors or liberal clergymen, they were deeply disturbed by the shattered economic and social orthodoxies in which they were raised; if they lost their compensating belief in Russia life would become too bleak to endure.”

Lyons tells a story that illustrates exactly how, and how much, journalistic coverage can change events in the world.

While on their visit to the USSR, a telegram comes to Shaw and Lady Astor from,

“a Professor Krynin, of Yale University, and begged for their intercession to get his family out of Russia. … A request by the eminent Britishers, he thought, might obtain the release of his family. … With Shaw and Lady Astor in Moscow, the censors could scarcely interfere with the sending of our dispatches, and the story was a three-day sensation in the American press. … Lady Astor … used publicity through the correspondents in the hope of forcing action. … And after she left, of course, the matter was forgotten.”

“Four or five months later,” Lyons is contacted by the ACLU about Mrs. Krynin. When Lyons visits the Moscow apartment building where all the correspondents had previously found her, she is no longer there, and a little boy tells him, “They came and took her a long time ago.”

After The Times has benefited from Duranty and his work, they pretended to care about journalism again, and got defensive:

“Duranty’s cabled dispatches had to pass Soviet censorship, and Stalin’s propaganda machine was powerful and omnipresent.”

If that’s the case, you should at least admit in your coverage that the stories you are printing have been censored by fucking Stalin.

The Times continues,

“Duranty’s analysis relied on official sources as his primary source of information, accounting for the most significant flaw in his coverage – his consistent underestimation of Stalin’s brutality.”

If underestimating a leader’s brutality, and relying on official sources, is so flawed – why is The Times repeating this pattern with Trump (as they did with Bush/Cheney)?

Maybe it’s not a flaw or accident – but done on purpose with plausible deniability (however implausible) to prop up dictators of choice and their flattering journalists. This purposeful duplicity undermines journalism, and truth-telling – and can create a terrible vacuum that vanishes all eggs and omelettes and journalists. Duranty wrote for the rich and powerful, and The Times publishes for the rich and powerful. They will always choose Stalin over a peasant; George Bush over a kid whose school he closed or Iraqi he killed; and Trump over all of us.

Just you wait, ‘enry ‘iggins, just you wait.