In 1691, Governor Ingoldesby’s “Humble Address” to the King described New York as “situate upon a barren island.” And that, “The middle of the Island [is] altogether barren… All the rest of the Province, West Chester, Staten Island and Martin’s Vineyard excepted, consist of barren mountain hills not improveable by humane industry.”

The Governor and Council did have a vested interest in the King thinking they could not produce their own goods, and thus increasing expenditures and trade, being in the King’s best interests, even closing their letter with a request for “a fresh supply” of “stores” because the “small quantity” that had been “brought over are mostly disposed of in the several small forts of Albany and Schenectady.”

Why do New York’s resources always go upstate?, he asked half-jestingly.

New York has “nothing to support it but trade,” the Governor complains, describing colonial New York’s economy, “which chiefly flows from flower and bread they make of the Corne the West end of Long Island and Zopus produce[s]; which is sent to the West Indies, and there is brought in return from thence amongst other things a liquor called Rumm, the duty whereof considerably encreaseath your Majesties revenue.”

This is the long introduction to the Barren Island, a little piece of land near Jamiaca Bay.

The recent book Brooklyn’s Barren Island by Miriam Sicherman describes Barren Island as a place where a “group of new immigrants and African Americans quietly processed mountains of garbage and dead animals starting in the 1850s … into useful industrial products.”

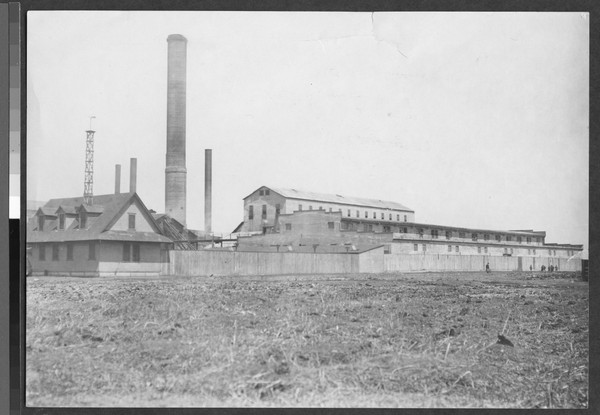

As described in A History of Public Health In New York City, “Barren Island was the site of several factories engaged in converting offal, fish, garbage, and foul-smelling material into fertilizer. One of the worst plants, described as being in a “very filthy and offensive condition,” was forced out of business, and several others were ordered to eliminate certain offensive procedures.”

And so the history of Barren Island is one of endless creativity and usefullness, at the bottom of the ladder, and how much everyone in the city who benefited from it disliked it.

The first mention of Barren Island we could find in the newspapers was from 1825, when New York State announced that it belonged to them.

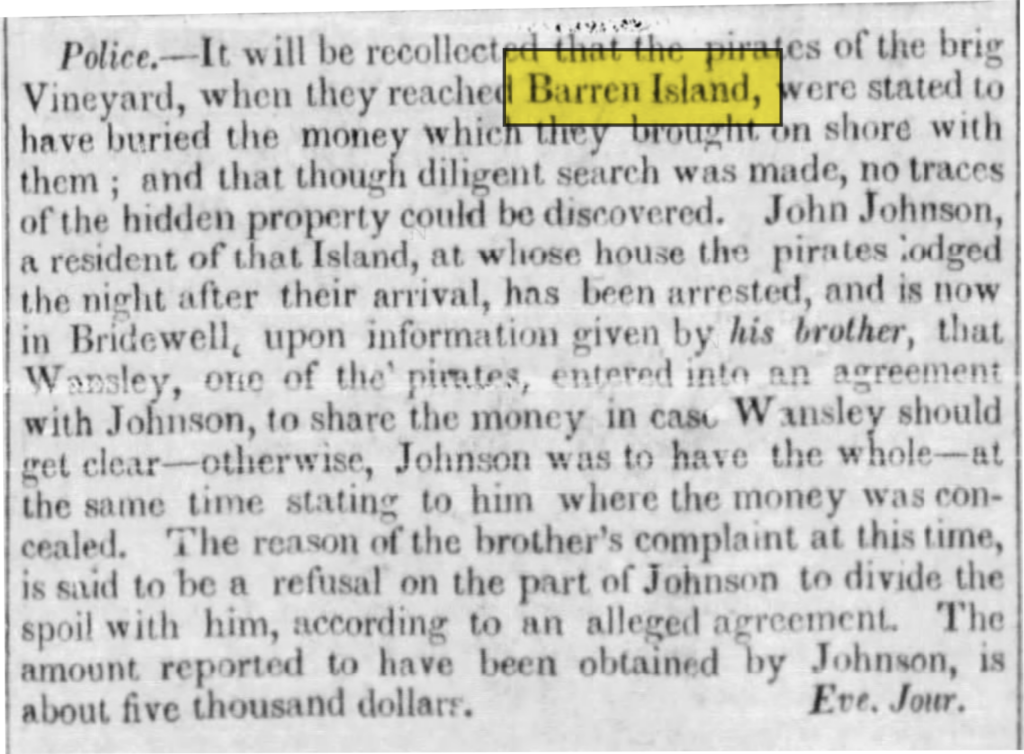

Subsequently, Barren Island shows up in the early 1800s in the papers – for pirates, for their subsequent treasure – and as a place for city pleasure-seekers to relax, swim, fish, and generally party.

As for pirates and treasure:

In 1834 The Long Island Star describes a “chowder party in company with ‘the troupers’ on Barren Island.”

An 1851 piece describes the plentiful fishing grounds there:

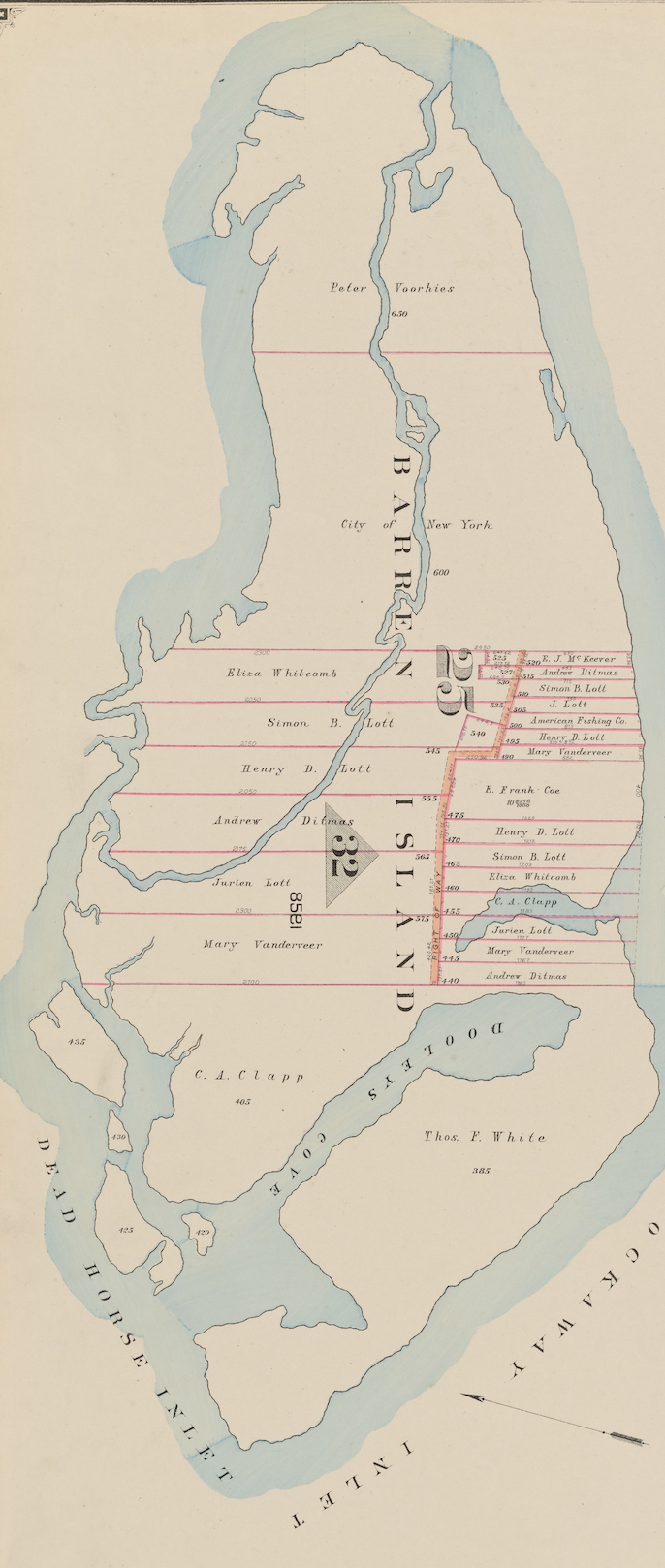

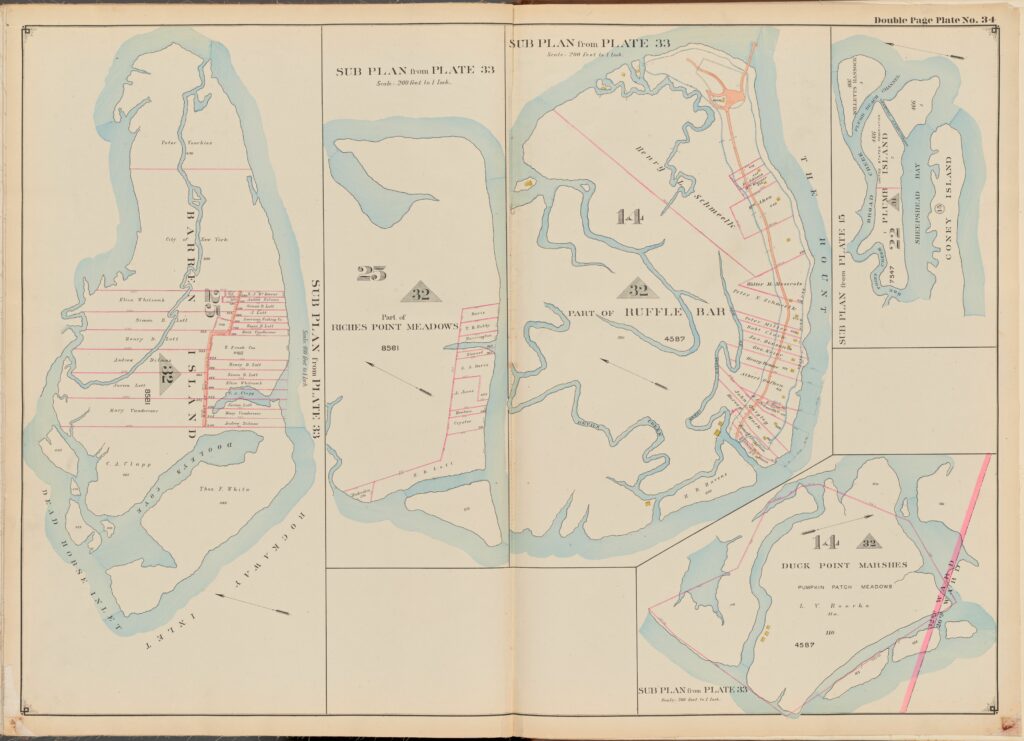

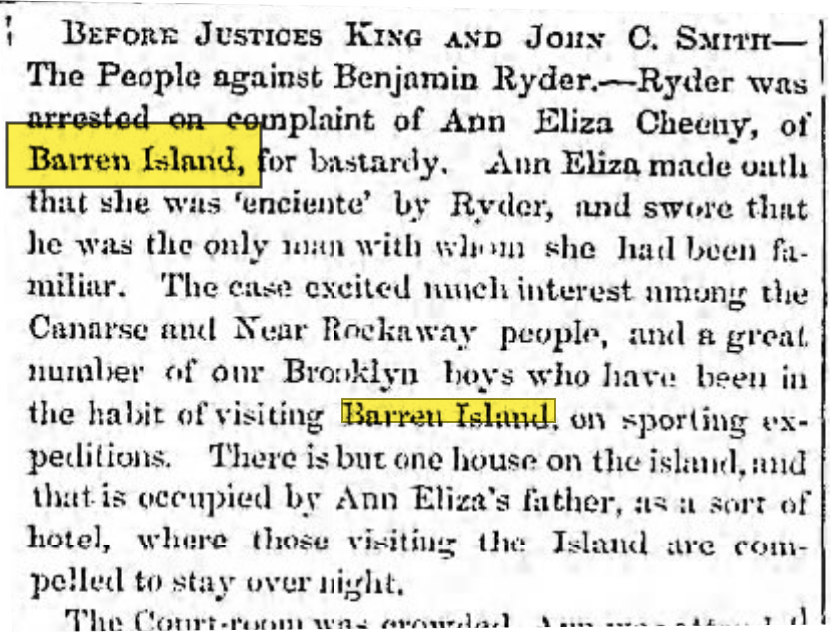

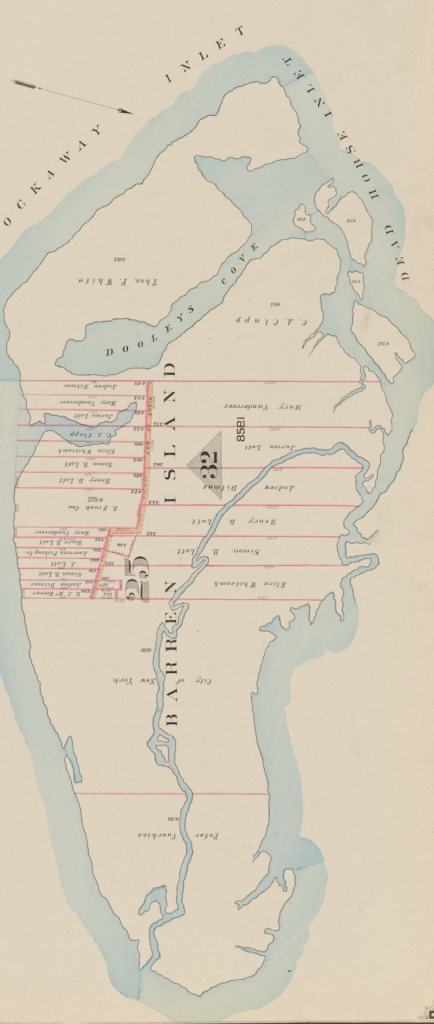

In 1844 a piece in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle shows two pieces of property mapped out on Barren Island, belonging to George Lott, and Peter Voorhees – but by 1849, The Eagle reports on a local scandal in “the only house” on Barren Island, owned by Ann Eliza Cheeny.

1853 sees Cheeny still living on the island having his chickens stolen.

“Mr. Cheeny alarmed Mr. Fritz, a neighbor of his, who jointly made after the thieves. They caught the ringleader, whose name is Woolly, but the other two succeeded in reaching the small boat with which they went towards [their] schooner. Two boys who were left in charge of the [schooner], say they never reached her; and there is scarcely a doubt but that they met a watery grave. Woolly was taken to New Lots for next morning, where he was examined.”

It was in 1853 that the Voorhees land, “now or late of Eliza Ann Voorhees,” was sold at Public Auction when the mortgage could no longer be paid, and it must be at this time that the Island became available for Reynolds to lease as a garbage dump.

In 1850, the Tribune describes Barren Island’s role in the growing city, while complaining about the amount of “dead animals, butchers’ blood, and other refuse [in] the streets” because New York’s Comptroller was not paying the bill to the private contractor who did the work, W. B. Reynolds.

A month’s bill for W. B. Reynolds’ services removing roadkill to his “reduction plant” is staggering in the number of dead animals:

500 dead horses and cows

100-200 dogs and cats

“blood, offal from shambles, nuisances from soap-boilers, and garbage and bones.”

For an example of how non-industrial soap was made at the time, we consult the WPA Slave Narratives from Georgia, where a man named David Goodman Gullins relates that in slave times, “We always had meat left over from year to year, and this old meat was made into soap, by using grease and lye and boiling all in a big iron pot. After the mixture bec[a]me cold, it was a solid mass, which was cut and used for soap.”

These ingredients would not be much different for the industrial soap-making manufactories in Brooklyn, which produced endless “nuisance” complaints for smell.

In this case, the Tribune tells us, “The offal and refuse is carried by Mr. Reynolds to Barren Island, just beyond Sandy Hook, where he manufactures from it prussian blue, glue, bone-dust and manure on a large scale. He employs a steamboat and two sailing vessels in transportation to and from the island…”

But by 1852 the island started being used for garbage. When a huge “quantity of corn” lay “in a rotten state in a store” at South and James Streets, where “two persons in the building had died of cholera” – they take it to Barren Island.

The two dead persons are a man and his child; the wif e is sick and enciente – the term used at the time to mean “pregnant.”

The 1,500 bushels of corn are described as “rotten … and smelling in the most horrible manner” – and are then “removed immediately to Barren Island, by the steamboat employed for the purpose of removing all the offal of the city.”

An 1853 article on the New York Horse Trade ends, “After the animals are worn out, they are taken to Barren Island, where manufactories are employed in converting their remains into oil, manure, etc.”

A letter to the editor in a 1907 New York Times expresses the changing sentiment towards the island:

“Two destructive fires and the sinking of a slice of Barren Island into the depths of Jamaica Bay, within a period of only a few weeks, gives rise to the thought that perhaps Providence has intervened to do for us what the city and State authorities have been unable to accomplish – do away with this group of noisome factories at the gateway of New York Harbor.”

A History of Public Health In New York City cites an aboutface in 1921 by the New York Academy of Medicine who “complained about living conditions among the garbage-sorting workers on Barren Island, noting the poor food supply and lack of medical service.”

In 1915 Barren Island had three plants that were such terrible nuisances that they were investigated officially by the City. The three were:

- Garbage Reduction plant

- Fertilizer plant … where garbage tankage is … dried

- The Horse plant … which renders animals, Hotel garbage and, during parts of the year, fish.

By 1940, the War Department wanted the island for its own, and in 1942 seized the island using eminent domain.

It also seemed the area was reclaiming its pastoral past in the public’s point of view. A Daily News piece from August 1940 called “Outdoors” gives recommendations for fishing near the island.

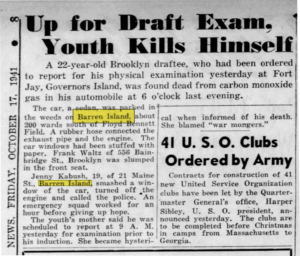

In a story sad and illustrative, a young man drafted into the war everyone could see coming, killed himself “in the weeds” on the island.

After the Navy turned it into the Floyd Bennett Field as New York first municipal airport, and then a naval air station for the second World War, Barren Island became the William Fitts Ryan Visitor Center, a park and recreational area.

Miriam Sicherman’s description of Barren Island as a place where a “group of new immigrants and African Americans quietly processed mountains of garbage and dead animals starting in the 1850s … into useful industrial products” reminded us of a wonderful 2011 article in The Brooklyn Rail by Eleanor J. Bader detailing the efforts of two people in Brooklyn to make recycling bottles and cans easier for the homeless who save them from landfills by removing them from the trash. Bader writes,

“Eugene Gadsden … known on the streets as the King of Canners – and Ana Martinez de Luco, a Catholic nun who became homeless in 2004 … [began] brainstorming about ways to improve the canner’s lot.”

The two of them opened a redemption center called Sure We Can, where people can bring their cans to be recycled without having to suffer the derision and disrespect that so many can collectors face when trying to redeem them at a regular store.

De Luco is quoted as saying, “Work is very important part of our lives. If you have something to do when you get up in the morning it gives meaning to the day. Canning is not the type of work that makes you tired. It’s like treasure hunting. And it’s good the environment. The three hundred or so canners who are part of Sure We Can bring in about 500,000 pieces a month.”

Bader cites statistics from the Department of Environmental Conservation to illustrate the enormous impact these workers have made: “Between 1982 and 2008, 90 billion containers were recycled, saving more than 52 million barrels of oil and eliminating 200,000 tons of greenhouse gases.”

an audio verison of this article can be

heard on the Internet Archive here