Book: When Africa Awakes by Hubert H. Harrison

Jeffrey B. Perry (Ed.)

Diasporic Africa Press

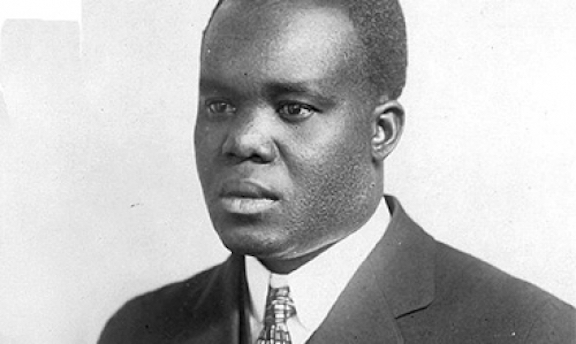

Hubert H. Harrison is the W.E.B. Du Bois, C.L.R. James, Ida B. Wells, Marcus Garvey that we’ve never heard of. Described by Richard B. Moore as the “Black Socrates” and by A. Philip Randolph as “the father of Harlem radicalism,” “the St. Croix, Virgin Islands-born, Harlem-based Hubert Harrison was a brilliant writer, orator, editor, educator, critic, and political activist” summarizes Harrison biographer Jeffrey B. Perry.

Originally published in 1920, this new edition of When Africa Awakes: The “Inside Story” of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World features Perry providing invaluable source notes and context to help illuminate Harrison and his influence.

“Hubert Harrison played unique, signal roles,” writes Perry in the book’s introduction, “in the largest class radical movement (socialism) and the largest race radical movement (the “New Negro” / Garvey movement) of his era.” Harrison was arguably the founder of the New Negro movement, was instrumental in convincing the International Socialist Review to capitalize ‘Negro’, and acknowledged the good work done by the then new NAACP but also called it out as the “National Association for the Advancement of Certain People” or “National Association for the Acceptance of Color Proscription.”

One comes away from Harrison’s writings with lists of histories to read, as well as a rich collection of Black/Negro/African-American writers of fiction, poetry and music. As a great scholar, Harrison shared his learning – what was useful, what was not; what was true to life, and what was true to prejudice.

Perhaps Harrison is not so famous as his contemporaries because he did not change with the times and those Black leaders “who sold us out during the war.” While Du Bois was leaving the Socialist Party so that he could support Woodrow Wilson, and while he later supported Wilson’s campaign to bring the U.S. into WWI as he applied for a position with the Military Intelligence Bureau (“that branch of government that monitored radicals and the African American community” writes Perry), Harrison left the Socialist Party because it was “Race First and class after” thereby forsaking non-whites. And Harrison did not support WWI, finding ingenious ways around the pervasive censorship of the time, writing “The white world has been playing with the catchwords of democracy while ruthlessly ruling an overwhelming majority of black, brown and yellow peoples to whom these catchwords were never intended to apply. But these many-colored millions have taken part in the war ‘to make the world safe for democracy,’ and they are now insisting that democracy shall be made safe for them.”

The prose, insight and ideas of When African Awakes are as fresh as any Du Bois, and indeed, fresher than any Mencken; and lead the reader not just into an understanding of Harrison’s own time and place, but of times and places earlier than his own; and of what Harrison’s own time and place thought of those that came before. They also stress the importance of learning that, as Harrison insisted, “Politically, the Negro is the touchstone of the modern democratic idea. The presence of the Negro puts our democracy to the test and reveals the falsity of it,” and that true democracy and equality for “Negroes” implies “a revolution . . . startling to even think of.”