The title of this article is almost verbatim the title of chapter 23 of Robinson Crusoe. No doubt untold numbers of scholars and writers have detailed the racism in this classic novel; have explained Crusoe’s white-European understanding of his “servant” Friday as “the noble savage” who accepts European culture without being civilized like a European.

But having just paged through this volume in idle hours, a few brief quotations might inform any possible readers without a JSTOR account (where one can read explanations like “An epistemological crisis is a semiotic crisis is a hermeneutic crisis…”).

Crusoe, like many a missionary before him, finds it impossible to really convince Friday of anything.

Nicholas Hudson does explain that,

“In recent years, critics have generally agreed that Defoe absolutely rejects the idea of the noble savage, and gives an essentially Hobbesian or Calvinist account of man in his natural state…”

Although J. Paul Hunter tempers this:

“Defoe steered a middle course, so that Friday seems noble – intelligent, willing to learn, possessed of some inclinations toward good – but misguided by his inadequate cannibalistic ‘natural’ religion; he needs the salvation provided by revealed Christianity.”

Mawuena Logan presses further:

“…Crusoe undertakes to erase Friday’s past and to convert him. This erasure recalls the erasure and distortion of the history and culture of the colonized and oppressed people.”

Contrary to what most of us believe, it was well-known in Europe that the Americas were being desolated and the people there enslaved or murdered. The life of priest Bartolome de Las Casas illustrates this, including his famous “Valladolid debates” in Spain with Juan Gines de Supulveda, which were known continent-wide.

The mistreatment of people in the Americas brought up challenging questions for any Christians who actually believed the purpose of Contact was to spread Jesus – how can you spread Jesus to a dead person? Europeans had to deal with the idea, Nicholas Hudson writes, that

“This persecution would suggest either that providence has unjustly permitted helpless people to suffer for no good reason or, alternately, that God sometimes judges the world according to a standard of moral truth incomprehensible to mortals.”

Most prefer that last interpretation – it leaves them open to be the interpreters who condemn anyone else claiming to be an interpreter without a different interpretation.

Logan articulates the unending catch-22 of “assimilation”:

“It is noteworthy that Friday’s acculturation, his ability to speak Crusoe’s language later in the novel, gives him no power, but instead enslaves him; in fact Friday is able to serve Crusoe more efficiently, to obey his orders ‘dig’ and ‘fetch.’ Thus, Friday’s acculturation should be seen as a situation wherein Crusoe (the colonizer or enslaver) lets Friday (the colonized/slave) gain access to Crusoe’s culture (e.i. language, religion) in order to better serve him – the plight of today’s ‘postcolonial’ subject.”

(Scott’s Against the Grain argues that writing was not invented as a means of self-expression or deep communication, but for state-record-keeping:

“One suspects that in the earliest states, writing developed first as a technique of statecraft and was therefore as fragile and evanescent an achievement as the state itself.”)

In the end, Crusoe’s efforts at “civilizing” Friday are a failure, because the Euro-American idea of civilization is a colossal failure that leaves out most everyone. Daniel Cottom explains that the island

“shows that the method of using an outsider to criticize civilization only serves to reaffirm civilization in all its ‘artificial’ values”; and that Crusoe, like all humans, “can only discover his nature by dominating and exploiting others, whether in fantasy or reality, so that the very ideas of nature and of the natural man are rent by insoluble contradictions.”

But Cottom points out that even Crusoe rejected the domination that Europeans brought to the hemisphere:

“At one point, for instance, he [Crusoe] allows that barbarians ‘were yet, as to the Spaniards, very innocent People,’ and favorably compares cannibals to ‘those Christians … who often put to Death the Prisoners taken in Battle.’

Like the missionary in the Moss/McBaine documentary The Mission: a hilarious instance of a missionary – now linguist, Daniel Everett – finding out after several years that no one he’s been missionary-ing to believes in his Jesus, because the missionary admits he’s never met Jesus and,

“I don’t know anybody who saw him. And it turns out I don’t know anything whatsover about him as a person. … I’d give my life for Jesus, but if he walked past this room right now I wouldn’t know him. So to them, that’s just utterly absurd.”

Only the threat or use of violence can spread religion like a missionary wants. When Crusoe tries to proselytize or “witness” (the preferred evanjelly term) to Friday, Crusoe gets stumped by obvious questions only the faithful hadn’t thought of, like:

“If your God is more powerful than the devil, why doesn’t your God kill the devil so the devil stops doing all the wicked things?”

[I am reminded of a friend who playfully mocked his Youth Pastor by asking, “Can God make a burrito that is too big for God to eat?”)

Crusoe tries to tell Friday that God will punish the devil in the end, and that like all people he is “preserved to repent and be pardoned.”

But Friday catches him – then the devil can repent at the end and be pardoned, too?

Stuck and frustrated by reason, Crusoe pursues faith:

“Here I was run down again by him to the last degree … yet nothing but Divine revelation can form the knowledge of Jesus Christ, and of a redemption purchased for us.”

Stymied, like a preacher stumped by a disobedient unbelieving child who sends the child off on an errand (like fetching a switch), Crusoe retreats by giving orders:

“I therefore diverted the present discourse between me and my man, rising up hastily … sending him for something a good way off…”

Adding, “I said ‘Good day, sir!'”

Too late in his shipwrecked voyage, Crusoe learns that all his ambition to procure his own enslaved people directly from Africa has cost him more than it could ever give – his soul reaching heights beyond even Gordon Gekko:

“And what business had I to leave a settled fortune, a well-stocked plantation, improving and increasing, to turn super-cargo to Guinea to fetch [N]egroes, when patience and time would have so increased our stock at home, that we could have bought them at our own door from those whose business it was to fetch them; and though it had cost us something more, yet the difference of that price was by no means worth saving at so great a hazard.”

Then, Crusoe describes his unperceiving fear of

“falling into the hands of cannibals and savages, who would have seized on me with the same view as I did of a goat or a turtle, and have thought it no more a crime to kill and devour me, than I did of a pigeon or a curlew.”

Or generations of people, like Friday, who would be killed and devoured by the plantation system that Crusoe pines for, and seeks to remake on his island, writing that he

“taught [Friday] to say master, and then let him know that was to be my name.”

Clever, Crusoe. Classic missionary shit.

But, as any regular person who has tricked preacher or teacher or cop or boss would know, it is Friday that is tricking Crusoe. Crusoe describes Friday glowingly, using Friday’s radiance to illuminate the greatness of Crusoe for Crusoe:

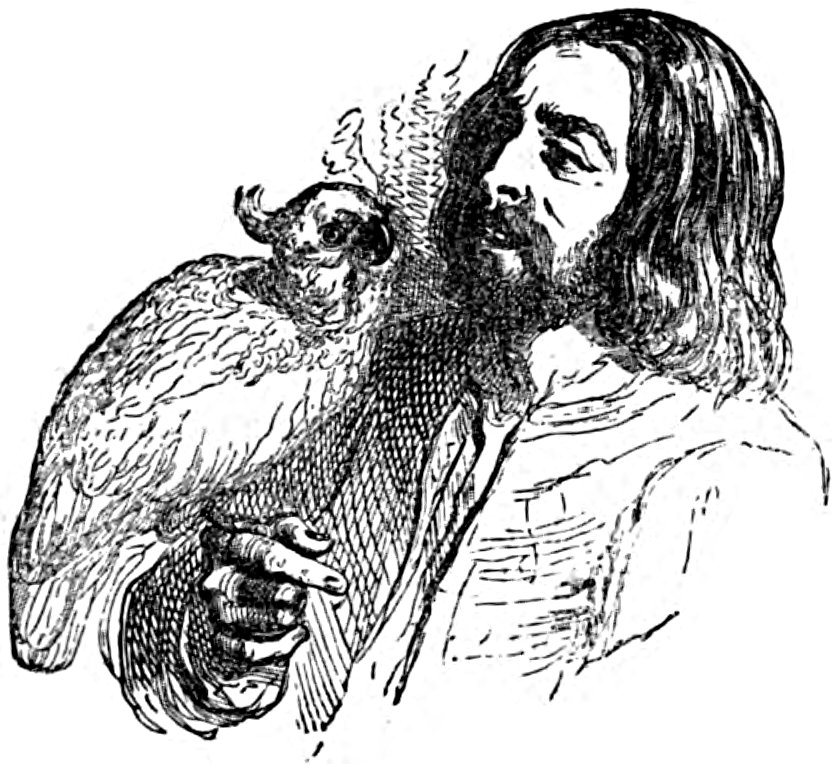

“…never man had a more faithful, loving, sincere servant than Friday was to me; without passions, sullennes, or designs, perfectly obliged and engaged; his very affections were tied to me, like those of a child to a father; and I dare say he would have sacrificed his life for the saving mine, upon any occasion whatsoever.”

A few pages later, Crusoe writes that Friday’s

“simple, unfeigned honesty appeared to me more and more every day, and I began really to love the creature; and, on his side, I believed he loved me more than it was possible for him ever to love anything before.”

Nonetheless, in contrast to these self-satisfied adulations, Crusoe later admits that,

“I made no doubt but that if Friday could get back to his own nation again, he would not only forget all his religion, but all his obligation to me.”

He sounds like every enslaver who ever professed that their enslaved people loved them and would never run away; and also that enslaved people were rotten renegades who would run away at the first chance.

This is not a new story – colonial history is full of Europeans who run off to the Indians and won’t come back; and captured Indians who refuse to stay with the Europeans. And Crusoe displays the same selfish delusion as many enslavers before and after him: to compensate for the bondage he places his servant into, Crusoe imagines that his servant loves the bondage with “sincerity” and “unfeigned honesty.” What else is an enslaver going to do? Admit that their servants hate them, look for any chance to get free, and nobody in their right mind would want to submit to relations that include bondage? Humble themselves in the eyes of the lord so that they might be lifted up?

Friday can easily see that if he doesn’t go along with Crusoe, he might die, and that Crusoe is one of those who would continue the beatings until morale improves, so better to avoid the beatings in the first place.

(Crusoe doesn’t seem to consider that Friday doesn’t respect him enough to think of him as anything greater than himself; Crusoe can shout to the rocks and sea that he is their master, too.)

Nevertheless, many scholars argue that Defoe was pursuing freedom of thought in his novel, and paid the price for it. Michael B. Prince writes that,

“the book’s first critics read it as a subversive deistical work. They did not find Crusoe’s adventures charming. Indeed, they considered the book a charm in the medieval sense: an object of alluring magic, a talisman of special properties communicating strange effects.”

Prince sees Crusoe as the embodiment of the “spiritual pilgrim and scoundrel.” Nicholas Hudson agrees that Crusoe

“illustrate[s] the conflicts and perplexities which accumulated when English Protestants began to insist on a theology that seemed acceptable to reason and common sense…”

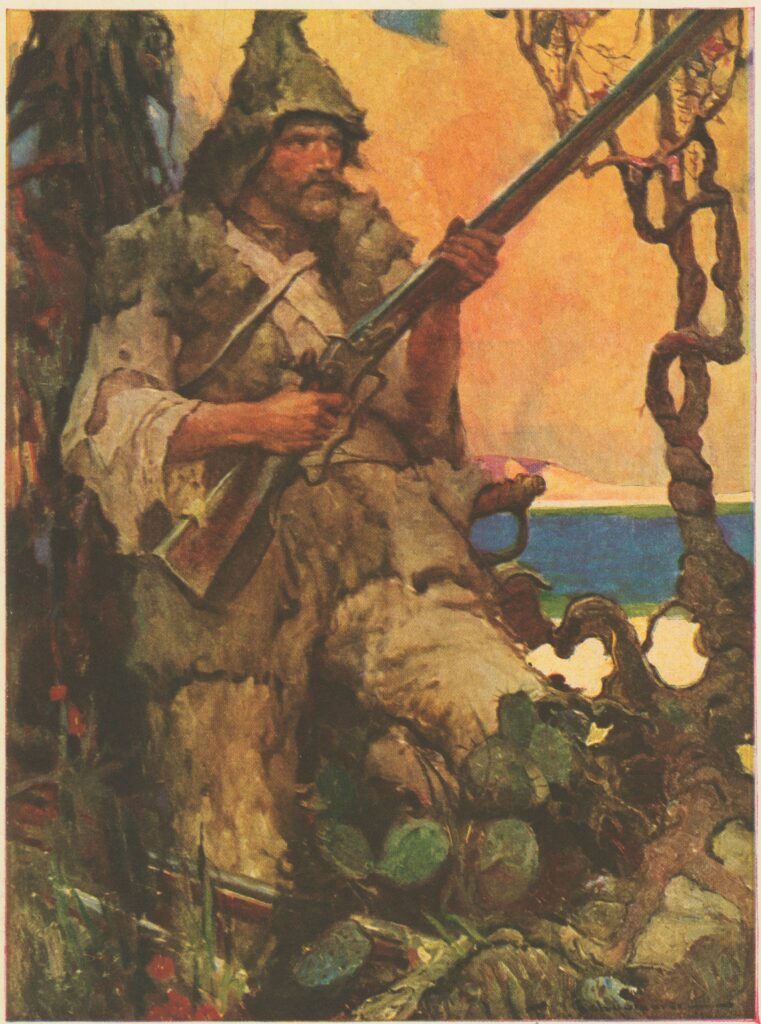

But rejecting reason, for faith, is what Christianity is all about – and Crusoe doesn’t miss out on missing out, Daniel Cottom describing Crusoe’s efforts to protect himself on the island:

“Not only must Crusoe define himself through the oppression of others: but he must even appear in a negative, oppressed relation to himself in his life just as he does in his journal when he balances his condition against worse fates that might have been his. At the end of the novel as throughout it, his positive triumph on the island remains entirely invisible, imaginary, and fictional.”

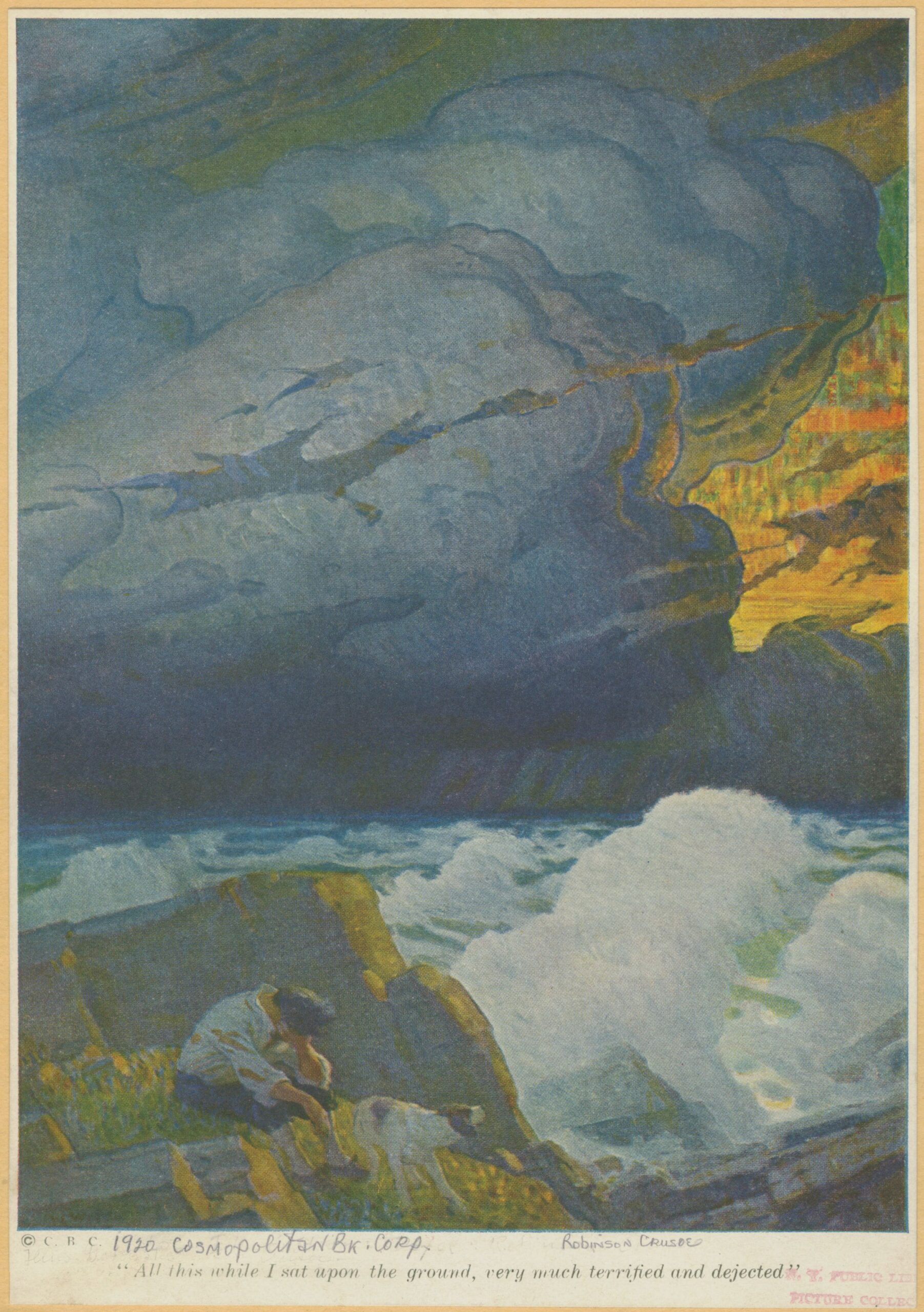

Like many victims of trauma, Crusoe’s comfort lies in imagining a worse fate, and being grateful to god that he escaped that fate for this one.

Crusoe was published in 1719: the Genocide Project in full swing, the creation of laws based on skin-color known as “white supremacy” many decades on the books in Virginia, New York and other pre-USA colonies.

But there is a deep despair in Crusoe being so close to the origin, so close to Bacon’s Rebellion – and yet his race-class-consciousness is only for white-Euro supremacy.

The novel addresses the world of European colonial skin color. Crusoe practically praises himself for not finding Friday physically repulsive:

“The color of his skin was not quite black, but very tawny; and yet not of an ugly, yellow, nauseous tawny, as the Brazilians and Virginians, and other natives of America are, but of a bright kind of a dun olive color, that had in it something agreeable, though not very easy to describe.”

The word “tawny” is a color-coded word that could only be socially meaningful in a white supremacist hellscape.

Hugo Prosper Leaming’s masterwork Hidden Americans: Maroons of Virginia and the Carolinas describes “tawny” people:

“…the Scratch Hall folk. These were a tawny or tan skinned people who lived along the southern edge of the Swamp on the North Carolina side of the Border. Scratch Hall was a region of mixed swamp land and pine barrens thick with underbrush…

“This tawny, English-speaking people, as isolated from outsiders as any other maroons, were seen as neither white nor black, and can therefore be taken as mainly the amalgamation of the Tuscaroras and the Roanoke settlers, together with other fugitives of indentured servant and Native American descent.

“The Scratch Hall people were the ‘wild’ cousins of the ‘domesticated’ Poor Whites of the open plantation countryside.”

Friday’s “tawny” color gives Crusoe cover for respecting him, in Crusoe’s mind, because he is not Black.

Crusoe even describes the very indoctrination process that teaches him that while he does not want to “fall into the hands of thieves and murderers,” it is acceptable for him to thieve and murder generations of enslaved people – ignoring how successfully he himself was molded into a form that would perpetuate existing power relations:

“…I observed that there is a priestcraft even amongst the most blinded, ignorant pagans in the world; and the policy of making a secret religion in order to preserve the veneration of the people to the clergy is not only to be found in the Roman, but perhaps among all religions in the world, even among the most brutish and barbarous savages.”

Like brutish and barbarous enslavers.

But this isn’t a worry, because

“we are all the clay in the hand of the potter, no vessel could say to Him, ‘Why has Thou formed me thus?'”

An excellent justification for staying in your place: God put you there. If you are enslaved, that’s because God wanted you to be enslaved. If you are the enslaver, that’s because God wanted you to be the enslaver.

Ignore that God’s people in the Old Testament were enslaved; and the bad guys were the enslavers. That’ll just confuse things. Stick with whatever priestcraft your priesthood has effulged – and if, at the Throne Of Judgment, God tells you that you were wrong, at least all your friends and neighbors will be with you in The Bad Place, and you won’t be bothered by all the wonderful people welcomed to The Good Place.

Just kidding: no enslaver ever truly believed in a next life. And those that preached the next life the most, believed in it the least. As Frederick Douglas wrote,

“Were I to be again reduced to the chains of slavery, next to that enslavement, I should regard being the slave of a religious master the greatest calamity that could befall me. For of all slaveholders with whom I have ever met, religious slaveholders are the worst. I have ever found them the meanest and basest, the most cruel and cowardly, of all others.”

“Robinson Crusoe not real?” cajoled a sincere teenage Ebenezer Scrooge to his sister, who insisted that Crusoe was not a real playmate for her brother.

But he was real, sister. Still is.